Don't Waste The Gift - What a Free Climber Can Teach Us About Flourishing

Over the weekend, the world’s greatest climber put on another masterpiece.

Alex Honnold, made famous by the National Geographic documentary Free Solo, went free solo again, this time in Taipei, Taiwan. After about 90 minutes of climbing the side of the 11th tallest skyscraper in the world, Alex stood atop a roughly four foot by four foot rounded platform, 1,667 feet above the ground. As was the case the entire way up, no harnesses, no safety nets, no parachutes.

With winds howling, Alex gazed out over the terrain of Taipei, soaking in not only the view, but the quiet satisfaction of having just become the highest free solo climber on a skyscraper in human history.

While Alex stood there with a sly smile, appearing as if he didn’t have a care in the world, the rest of the world tuned in with sweaty palms, motion sickness, and queasiness. Watching from the safety of the couch was enough to elevate heart rates and tighten shoulders.

How in the world was he able to climb the side of a skyscraper 1,667 feet up with no ropes?

Isn’t he afraid of falling?

How does he block out the fear?

Is this guy insane?

Beyond the vicarious, height inducing discomfort, Alex’s climb showcased several powerful elements relevant to flourishing.

Mastery.

The neuroscience of fear.

Being present when it matters most.

Innate Talent and Mastery

My wife and I stumbled onto Netflix’s live documentary of Alex’s climb having only loosely heard who he was before. As a snowstorm rolled through our region, we settled in for what felt like the perfect way to spend a winter evening.

Throughout the climb we kept looking at each other, commenting on how uncomfortable it felt just to watch. Our bodies were responding as if we were on the side of the building ourselves. Elevated heart rate, sweaty palms, that tight uneasy feeling in the chest. All the familiar signs of a nervous system detecting threat.

As Alex took breaks, he would sit on the very edge of the building, his legs dangling over the side, like someone perched at the edge of a pool in Cancun.

In reality, his feet were hanging roughly a thousand feet above the ground. A loss of balance would mean certain death. Yet Alex looked relaxed, smiling, as if he were sitting down for Sunday brunch.

After the third break, I had an epiphany.

Something has to be different about this guy’s brain.

The comfort he felt at those heights didn’t seem natural. I don’t care if you were born on the side of a mountain. The brain, particularly the amygdala, is designed to detect threat and preserve life. I made a comment to my wife and did a quick Google search.

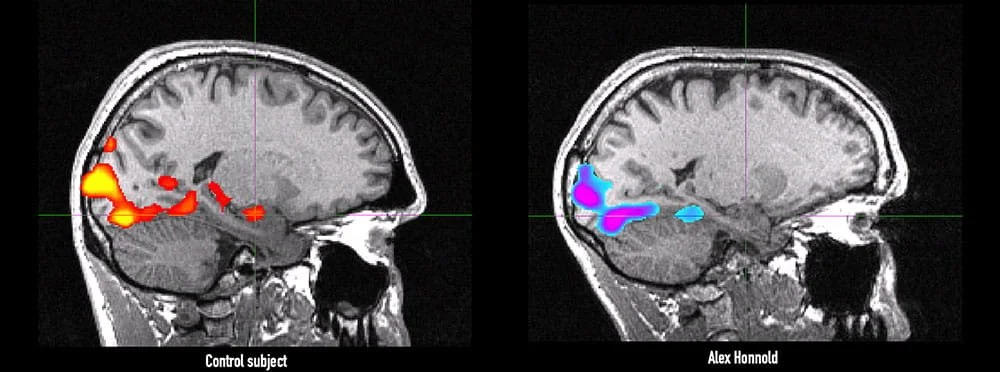

Seconds later, I found an article describing how neuroscientists had studied Alex’s brain using fMRI scans. His amygdala was not smaller than normal. It was the same size as everyone else’s. What was different was how it responded. His amygdala simply did not fire as quickly or as intensely when exposed to fear inducing stimuli.

In short, his brain registers threat differently than most.

Imagine having just a bit less fear in the moments that matter most. The biggest games. The highest pressure situations in your craft. To a degree, that is the world Alex Honnold experiences.

Before the “must be nice” crowd rolls in and chalks this up to another example of innate talent winning out, we need to frame the other half of the story. Mastery.

Mastery Earned Over Decades

While Alex was aided by advantageous neural wiring, he was calm because he had given his brain decades of evidence that he was capable. He had quite literally been there and done that thousands of times.

Alex has been climbing for over 30 years. He started around age 10 and has completed some of the most demanding climbs on the planet.

El Capitan

Half Dome in Yosemite

Moonlight Buttress in Zion National Park

El Sendero Luminoso in Mexico

He has mastered the physical movements of climbing. Foot placement, balance, efficiency, and control. He has also mastered his body through years of climbing specific training. Exceptional core strength, endurance, and grip strength developed not for the gym, but for the wall.

Like elite athletes in every sport, his body fits his craft. Michael Phelps looks designed to swim. LeBron James looks designed to dominate a basketball court. Alex Honnold’s physiology aligns perfectly with the demands of climbing.

But his mental training may be even more impressive.

It would be easy to assume that because Alex’s amygdala responds differently to fear, he does not feel fear at all. That assumption would be wrong.

“I’ve done a lot of thinking about fear. For me the crucial question is not how to climb without fear, that’s impossible, but how to deal with it when it creeps into your nerve endings.” Alex shared in his book.

Alex Honnold does feel fear. He has simply trained himself to deal with it better than most.

So how does he do that?

Training the Mind to Deal With Fear

The same way every high performer learns to handle fear, nerves, and high stakes moments.

Exposure

Alex has placed himself in fear inducing situations so many times that discomfort has become familiar. Exposure builds comfort. Whether it is public speaking, big games, or going for the sale, repeated exposure trains the brain to respond with clarity rather than panic. There are no shortcuts here. You need reps, time in the seat, and shots on goal.

Visualization

Honnold is notorious for mentally rehearsing every detail of a climb. He does not just picture success. He rehearses exact movements, hand placements, body positions, and transitions. By the time he steps onto the wall, his mind has already been there thousands of times. This is not manifestation. It is preparation. And it is something anyone can train.

It is not innate talent or mastery.

It is innate talent and mastery.

What Is Your Version of Free Soloing?

Every once in a while, we get to watch a master take on an unthinkable challenge. Whether it is Eliud Kipchoge chasing the 1:59 marathon or Alex Honnold climbing a skyscraper, it gives us a powerful visual of flourishing performance.

It also forces a deeper question about mastery itself.

It seems half the battle is discovering what you are naturally suited for. The other half is sustaining decades of effort and improvement that looks like work to everyone else, but feels immersive to you.

Alex’s body type suits climbing. His brain registers fear differently. Those are surely gifts.

But gifts without training won’t get you to the top of skyscrapers.

We all have innate gifts that make us well suited for certain pursuits and poorly suited for others. Finding what you are naturally aligned with matters just as much as finding the discipline to train.

You cannot fight your nature. If you are an early riser, rise early. If you are a night owl, owl the night. If you are built for sprinting and lifting, sprint and lift. If endurance suits you, move for long periods of time.

Forcing yourself into the wrong arena is like a lion fighting in the ocean or a whale hunting on land. Why would you allow the game of life to drift toward environments where your return on effort is diminished?

Put yourself in the best position by aligning your innate gifting with environments and pursuits that allow it to flourish.

But once you have found that alignment, it is time to work.

In Alex Honnold’s case, what good would his unique amygdala response be if he had not trained his body for decades? What value would a diminished fear of heights be when he physically wouldn’t be capable of getting off the ground!

The gift creates potential.

The training makes it visible.

The question for all of us becomes,

Have you identified your natural gifting but neglected the training required to steward it well?

Or have you been grinding for years in environments that do not actually reward what you are best at?

To do either is to waste the gift.

Find what your innate talent is best suited for. Then pursue mastery with patience and consistency.

You don’t need to free solo a skyscraper, but if you want to live a flourishing life, aligning your natural wiring with decades of hard work is one of the best places to start.

Stay The Course,